Kerala Flooding: Natural Calamity or Manmade Disaster?

As India prepared to commemorate its 72nd Independence Day, the southern state of Kerala saw little reason to celebrate. The monsoon rainfall this year was heavier than normal and had reached alarming levels. On an average, districts received 30 percent excess rainfall, with some districts recording between 70 to 90 percent excess.

In agricultural India, an abundant monsoon is a blessing. However, successive spells of heavy and excess rainfall triggered massive flooding that devastated Kerala. The last time flooding of this level occurred was in 1924, when the total rainfall from June to August totalled 2852 mm.

By late August this year, more than 450 people had died, over a million were in relief camps, and the state estimated a loss of USD 2.8 billion in property damage – approximately 100,000 buildings, 10,000 km of roads and highways, and 280 bridges.

Mapping Affected Areas

Using pre- and post-flooding open source satellite images and image processing using GIS technology, WRI India generated maps of flood-impacted areas, which showed flooding over approximately 860 km2 of agricultural land, 100 km2 of built-up rural land, and 50 km2 of built-up urban area.

Extent of flooding in the Kochi Metropolitan area, 9 August, 2018. (Credit: Raj Bhagat Palanichamy/WRI India)

Extent of flooding in Kuttanad region, 21 August 2018. (Credit: Raj Bhagat Palanichamy/WRI India)

Extent of flooding in Palakkad region, 21 August 2018 (Credit: Raj Bhagat Palanichamy/WRI India)

In the aftermath of human and economic losses such as these, the question often arises: are these mere natural calamities or are they manmade disasters? The answer isn’t one or the other. While this was an extreme weather event, there are several manmade stresses that significantly exacerbated the situation, such as unsustainable development, the construction of dams, and the destruction of natural infrastructure.

Unsustainable Development

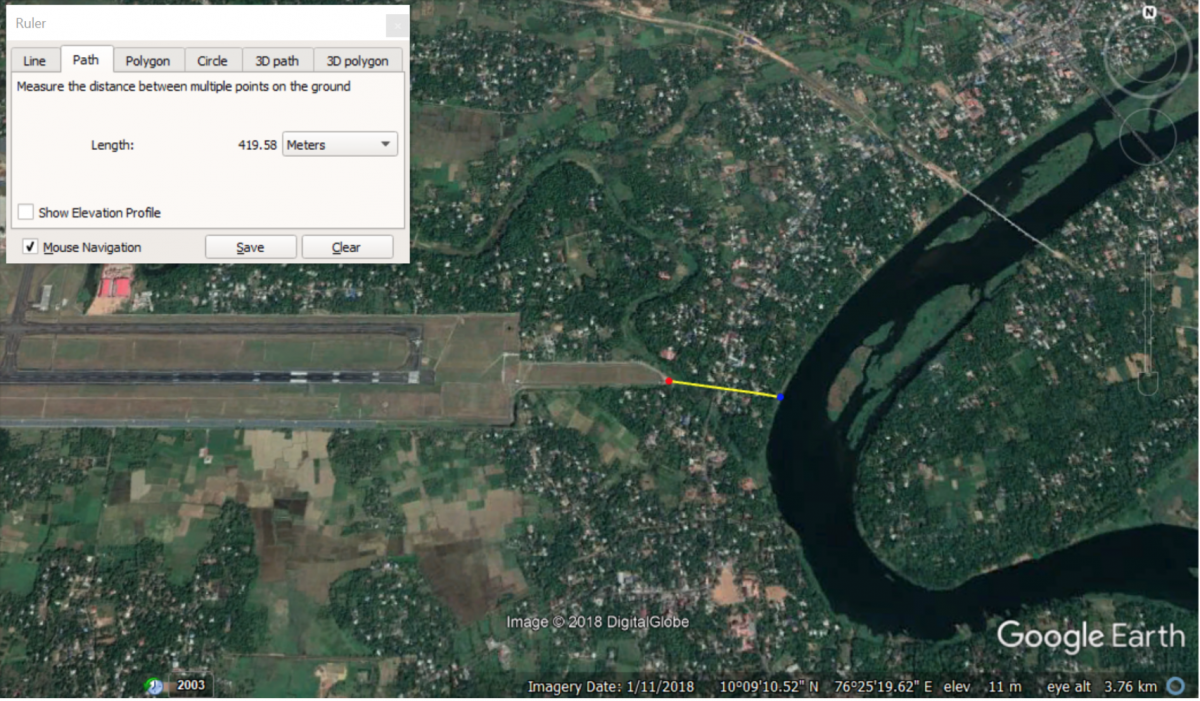

Urban floods are living testimonies of the conflict between urban development and weather-related vulnerabilities. An example of this was the closure of Cochin International Airport for two weeks when flood waters from the swollen river breached the periphery walls and flooded the runway. Additionally, the world’s first solar-powered airport lost approximately 20 percent of its solar panels owing to damage. In total, a loss of USD 35 million was incurred owing to damage to the airport and the ensuing closure.

The airport is a mere 420 metres away from the Periyar river, is located within the floodplains of the river, and was built by ‘realigning waterways’. The Chengalthodu creek, which connects to the Periyar river, was completely realigned.

Map showing the proximity of Cochin International Airport to the Periyar river and its floodplains. (Google Earth)

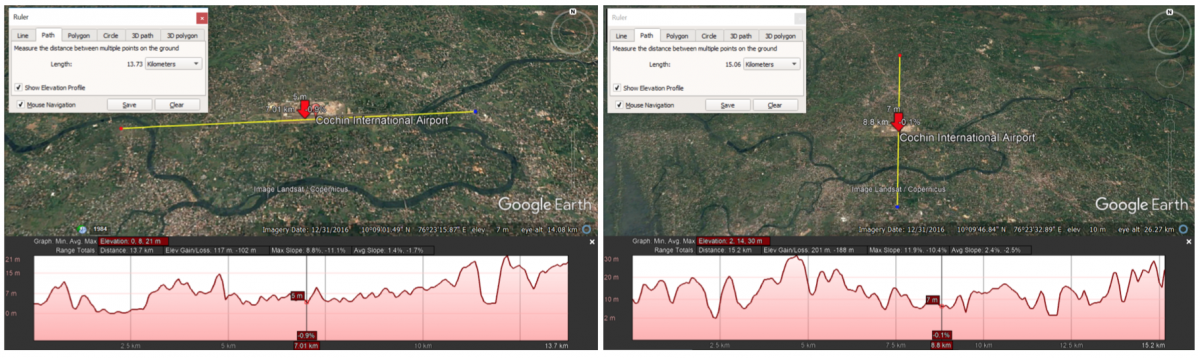

Any construction over river floodplains is always vulnerable to flooding. When the Periyar river is in spate, the airport’s drainage system, which discharges into the Chengalthodu creek, is compromised, and there is a reverse flow of water along the creek and drainage channels into the airport. In addition, an elevation analysis shows that the airport and the river are almost on the same level, and areas to the north are at a higher elevation. This means that in the event of heavy rainfall, storm water from the north drains towards the airport.

Elevation analysis of Cochin International Airport and the Periyar River. (Google Earth)

Kochi’s airport isn’t unique in this aspect. Airports in Mumbai and Chennai, which are also located close to rivers and have expanded their runways over river channels and floodplains also experienced extreme flooding and closure in 2005 and 2015 respectively.

Rising Reservoirs

Kerala has 53 reservoirs built over its rivers. These are managed by the Kerala State Electricity Board (KSEB), and produce hydro-power, which makes up for more than half the electricity demand in Kerala, and are crucial to the economic development of the state.

However, incessant, heavy rainfall across the state meant that upstream and downstream reservoirs were filled by July and river channels (which when dry can absorb large releases from dams) were also filled to capacity. In the event of reservoir failures or the release of water from upstream catchment dams, the entire downstream regions are affected within an hour placing most of the state in a high flood-risk zone. Furthermore, there are no flood warning stations in Kerala.

A CAG report from 2017 states that none of Kerala’s dams have emergency action plans (EAPs) or inundation forecasts simulating impacts and emergency responses in the event of a dam collapse. Again, this situation is not unique to Kerala. The CAG report states that only 7 percent of the large dams across India have such EAPs.

While KSEB followed basic protocols of three warnings to district administrators before dam release based on inflow-outflow data and heavy rainfall warnings from IMD, the absence of inundation maps and hydrological models of the region meant that local decision-makers were unaware of the possibility of cascading impacts of the floods.

Loss of Natural Infrastructure

The several incidences of landslides that aggravated damage to life and property could be attributed to extensive development, including mining, quarrying, and road building along the hillsides of the Western Ghats.

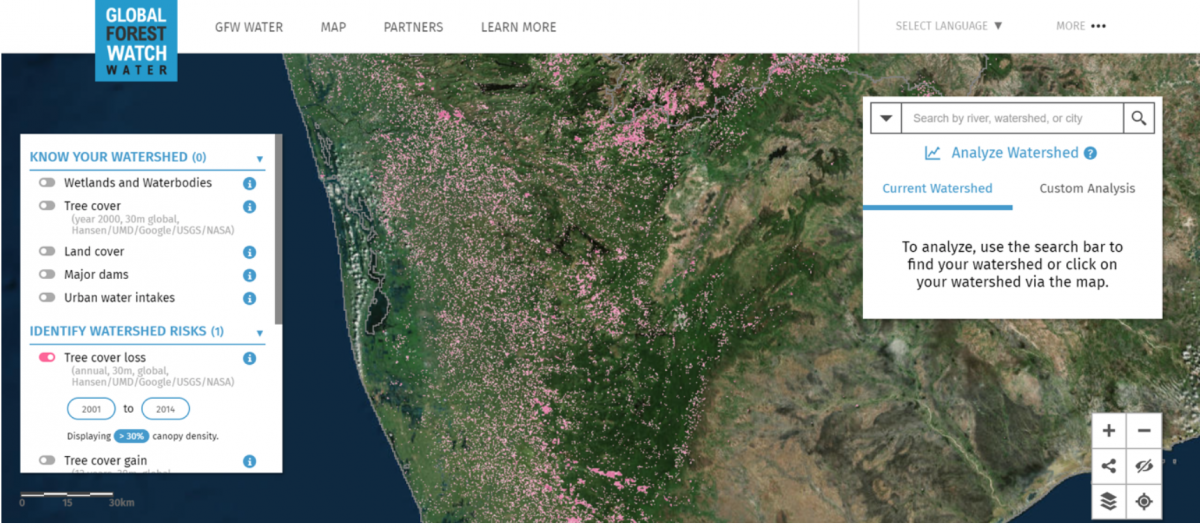

Research indicates that where forests are disturbed or replaced with plantations and other silviculture practices, a noticeable change in water quality and quantity is seen along with higher levels of erosion. The Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel (WGEEP) 2011 called for strict measures to be enforced to limit development and change in forest cover in the region. However, this was unequivocally rejected by the relevant state governments and the central government at the time, citing the need to meet livelihood and employment objectives for the inhabitants of this area and economic goals of the state.

Analysis from Global Forest Watch, shows significant tree cover loss between 2001 and 2014. Removal of forests in the catchment areas of dams, shifts to monoculture plantations, and illegal construction and farming on slopes exceeding 30 degrees are some of the manmade stress factors for the landslides and flood devastation.

Loss in tree cover in the region. (Global Forest Watch)

Flood Risk Resilience

While the impacts of this kind of extreme flooding events cannot be completely removed, better planning and preparedness can significantly reduce human and economic losses. Resilience is the ability of a system to resist, absorb, accommodate, adapt to, transform, and recover from the effects of a hazard in a timely and efficient manner, including through the preservation and restoration of its essential basic structures and functions through risk management.

Using available resources such as the Sendai Framework, the Aqueduct Global Flood Analyser, and modelling tools, scenario simulations under several flood return periods can be used to discuss and prioritise flood risk management strategies and subsequent investment in the state. For Kerala and other regions at risk of extreme flooding, disaster resilience measures are becoming increasingly crucial to incorporate into urban and economic development plans.