5 Opportunities for Micro-greening in Low-income Urban Settlements

Climate change-induced events such as heat waves and floods severely impact the quality of life in urban areas. It can be financially disruptive and even fatal, disproportionately impacting settlements most vulnerable to climate risks. Greening of open spaces can be an important strategy for addressing such increasing urban heat and flood-related risks in cities. However, as our cities expand, rampant urbanization adversely impacts the availability of and access to such open spaces.

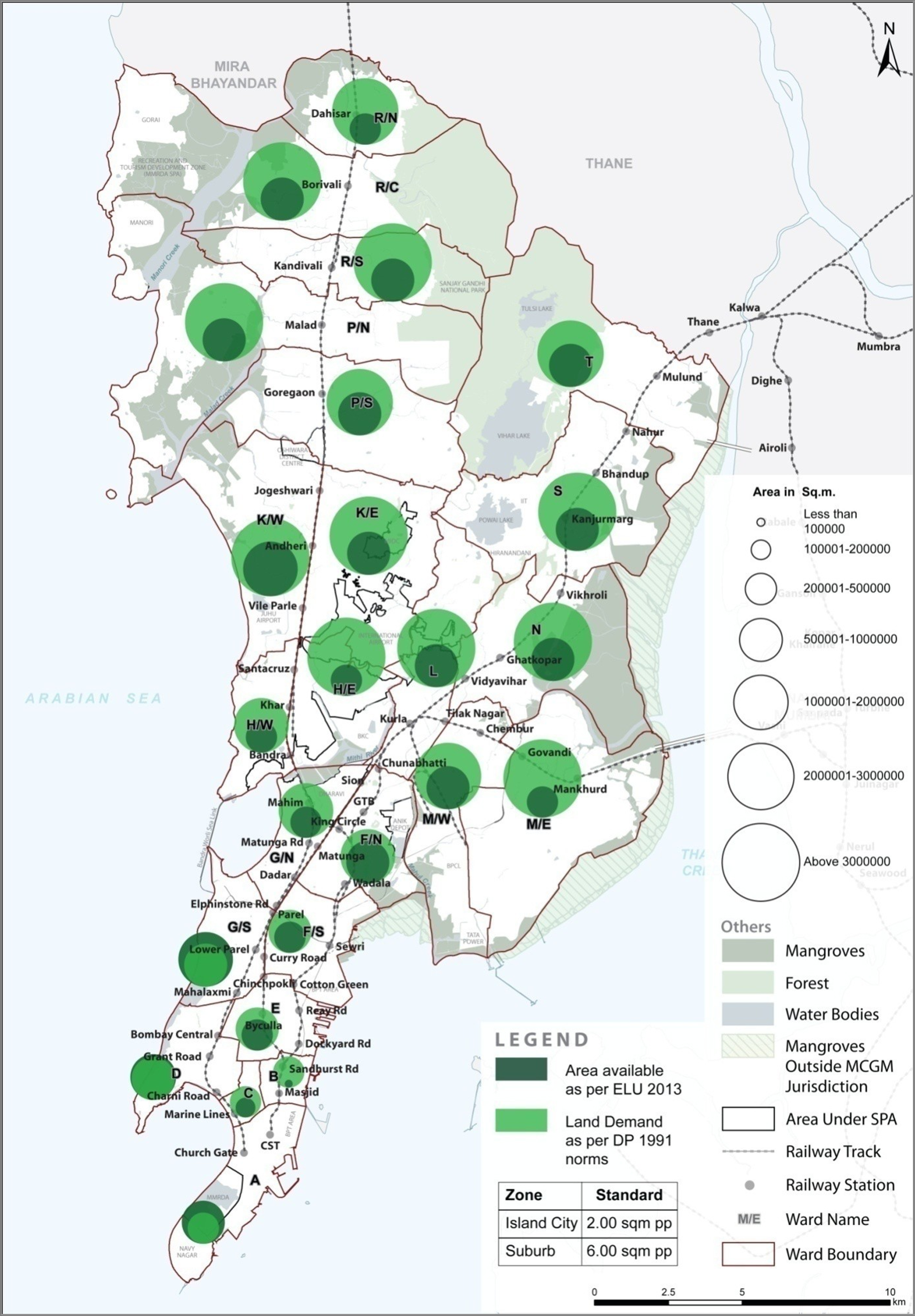

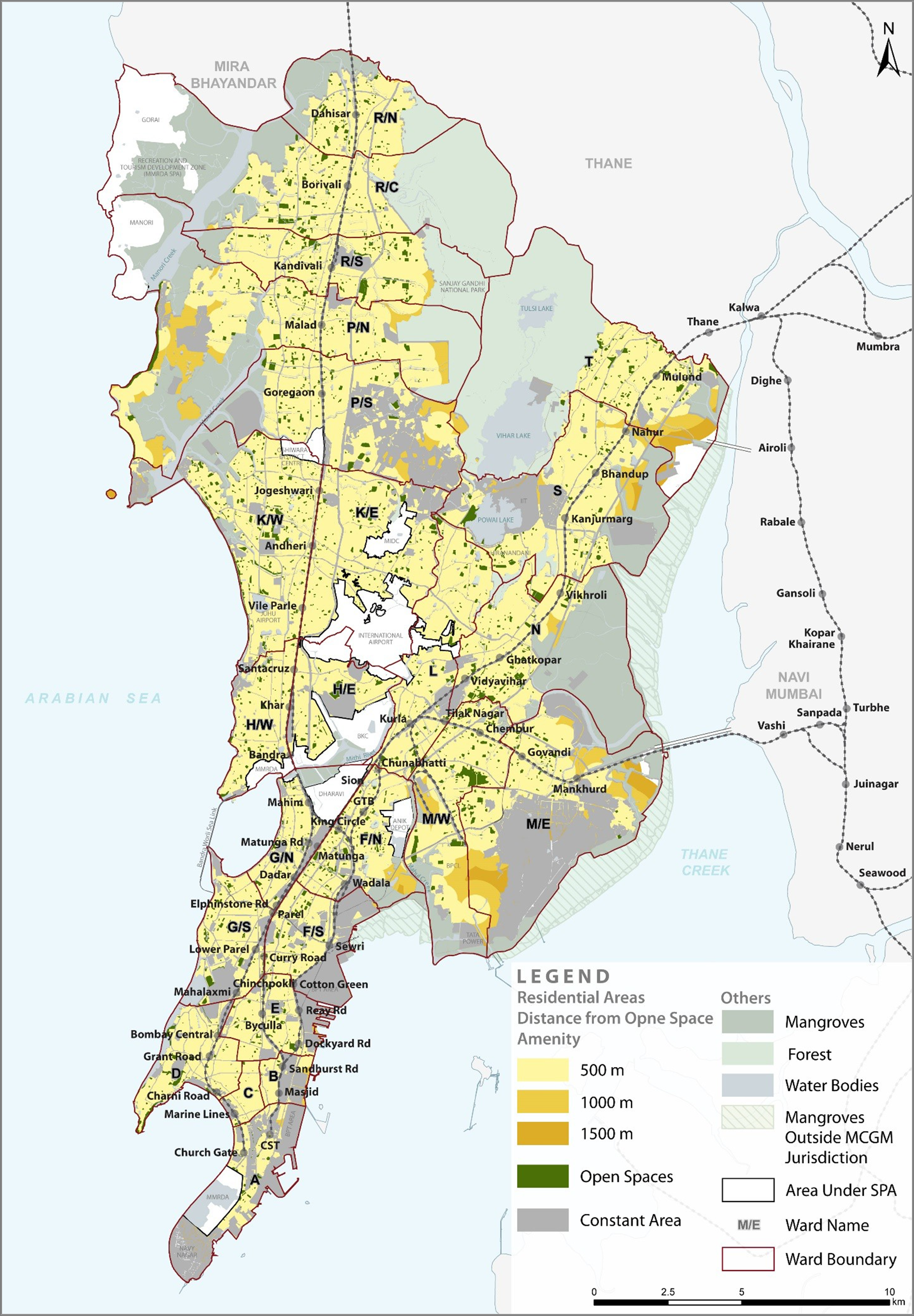

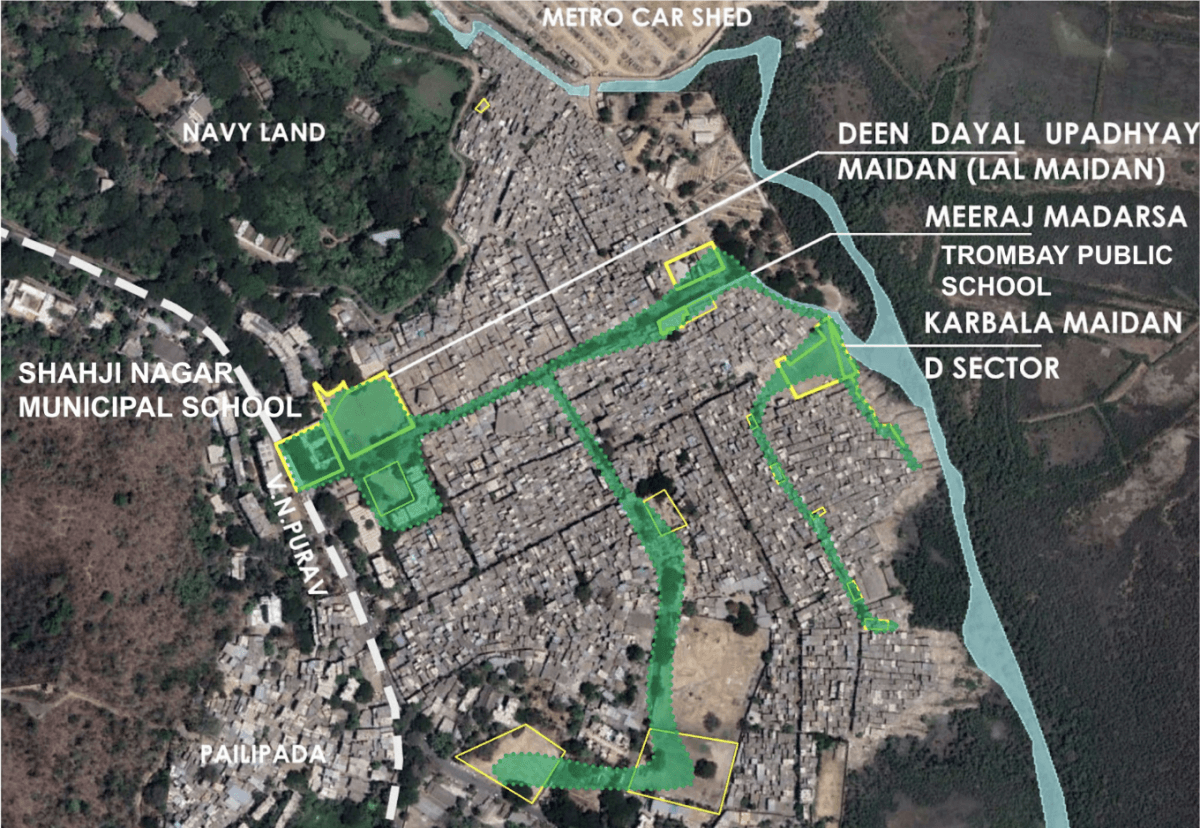

In Mumbai, where over 35% of the population lives within 250 meters of chronic flooding hotspots, high-density informal settlements and rehabilitation and resettlement colonies already face the brunt of this space crunch with limited open areas, which are often disputed and where greening is not prioritized. The M/East ward, which has the largest informal settlement population in Mumbai, is short of 17,90,000 square meters of potential open space to serve its population of 9,02,147, in accordance with the Mumbai Development Plan for 2034. Even if this space were to be leveraged, it would still be less than half of the city’s benchmark of 4 square meters of open space per person.

With large open spaces lacking in cities, the greening potential of smaller, leftover spaces such as private balconies, courtyards, rooftops and street chowks (intersections or roundabouts) can be tapped to enhance the area’s biodiversity and ecosystems.

Small-scale greening methods are not only cost and resource efficient but also complement the existing infrastructure. In this blog, we look at how people in Mumbai’s M/East ward and other vulnerable wards are greening their everyday spaces.

Balconies and Pocket Terraces

Balconies and small pocket terraces remain the most convenient individual as well as community-managed spaces. However, in a crowded chawl (चाळ) with multiple tenements, these shared spaces become prone to littering and spitting.

Gardening has the potential to improve psychosocial health and in low-income housing projects, it can become a community exercise that brings people together. Residents can consider different types of plants based on their interests, whether it be growing their own food or medicinal plants. Individual or household-driven interest in greening can transform neglected spaces, beautify them and enhance the area’s biodiversity.

Roofs and Walls

While roofs and walls support the structural strength of the house, they also absorb heat, increasing the overall temperature of the house. Placing plants on the roof and along the walls in informal settlements can create a heat-resilient barrier, helping the household maintain ambient indoor temperature. Communities could also consider extending the approach of greening roofs and walls to toilet blocks, health facilities and other institutional and public amenities in the neighborhood.

Common Spaces

Common spaces are often disputed in high-density communities, but they can be unlocked by making community members co-creators and stakeholders in its revitalization process. This could take the form of placemaking exercises such as the planning of seating areas and painting murals with local youth.

A derelict open space, perceived unsafe by the young girls of Lallubhai compound, was similarly transformed through participatory greening and placemaking. Today it is a vibrant, inclusive multi-functional space and the fulcrum of socio-cultural activities, study group meet-ups and festive celebrations.

An open area in Ambujwadi, in Mumbai’s P/North ward, experiences heavy waterlogging during the monsoon. During the dry season, it serves as unorganized parking, hampering resident movement. Community members wanted the area to be transformed into a space of recreation and play. WRI India, in conjunction with Youth for Unity and Voluntary Action (YUVA) and the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC), conducted participatory workshops and site visits to develop a long-term project plan that not only integrates sustainable greening interventions but also incorporates water drainage strategies.

Plot Peripheries

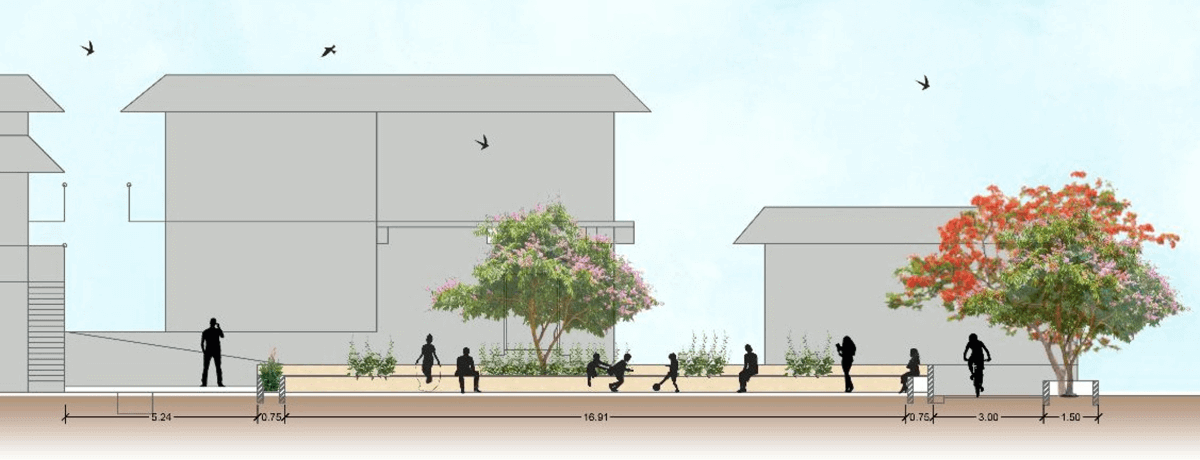

Periphery areas along residential societies, public buildings and institutional compounds are often left undesigned and unused. Even after leaving appropriate space for access roads and circulation areas, as mandated by the Development Control Regulations, stretches along compound walls remain, and can be used for greening through on-ground planting or raised planter beds. These areas can be developed as social spaces and learning environments to prevent misuse and encourage community access and engagement, as demonstrated in the example below.

A 100-square-meter periphery stretch in Shahaji Nagar School at Cheeta Camp was restored using activity-based training modules involving students and staff to integrate biodiversity into the curriculum and ensure the upkeep of the space. The site is today a learning aid for upskilling students and the staff and serves as a living laboratory featuring informative illustrations on ecology and biodiversity.

Along Existing Infrastructure

Greening can be practiced across different scales, along city fringes and infrastructural networks, to form spaces that aid food production, provide aesthetic relief, and reduce air pollution and heat stress. However, areas adjacent to railway lines, under flyovers or along street medians often get overlooked and become informal dumping or parking grounds. Appropriating such spaces using scientific greening methods, through urban farming and the use of planter beds and potted plants, or planting mini forests of native tree species, can transform them into productive landscapes.

Residents have a better understanding of the small spaces that exist between households or along the edges of settlements. Tapping into this community knowledge and interacting with the area’s stakeholders enables the selection of suitable sites. These small-scale interventions need to be augmented with field studies, training, capacity building and community consultations to strengthen and sustain on-ground implementation. These activities foster the integration of indigenous greening knowledge and community values associated with nature, along with empowering community members to nurture and scale up localized greening practices.

One initiative that advances the strategy of leveraging small, overlooked spaces is Mumbai’s first-ever greening handbook. It looks at greening interventions across various scales – small, medium, and large (S-M-L) – based on the area available to residents.

It is important to encourage scientific greening practices and the culture of planting with a plan. Along with contributing to local biodiversity, these greening efforts are also significant for and aligned with the climate adaptation and mitigation efforts that the BMC is adopting for overall climate resilience in the city.

All views expressed by the authors are personal.