What Does It Take To Shape a Welcoming Neighborhood?

India is home to ten of the world's fastest-growing cities. However, growth by itself is not a measure of quality. The quality of life in cities depends on equitable access to services and opportunities, as well as access to quality public spaces and safe streets. In India, city officials and urban practitioners help shape urban development which makes it important to build their capacity in designing neighborhoods that are safe, green, accessible, playful and inclusive.

Lessons From an Immersive Experiential Learning Model

The ‘Smart Cities Smart Urbanization’ conference held in Surat last year presented an opportunity for WRI India to support the building of an immersive experience featuring a life-size model of a neighborhood. Designed in collaboration with placemaking professionals from across the country, and deployed in just seven days, the pavilion 'Aamaro Padosh,' presented key decision-makers, city officials and urban practitioners with the opportunity to explore a neighborhood that has been designed to be welcoming, inclusive and accessible.

What Do Welcoming Neighborhoods Consist Of?

Neighborhood streets, intersections, parks and playgrounds have always served as anchors for interaction and have the potential to be reinforced as public spaces. This can be done by incorporating the following components:

- Streets prioritizing people: Streets are the first point of interaction once you step out. They should be designed with continuous, designated cycling and walking corridors, public transit connections and last-mile opportunities. Neighborhood streets should also have slow-moving traffic, ease of walkability, and intermittent pause points to encourage social interaction.

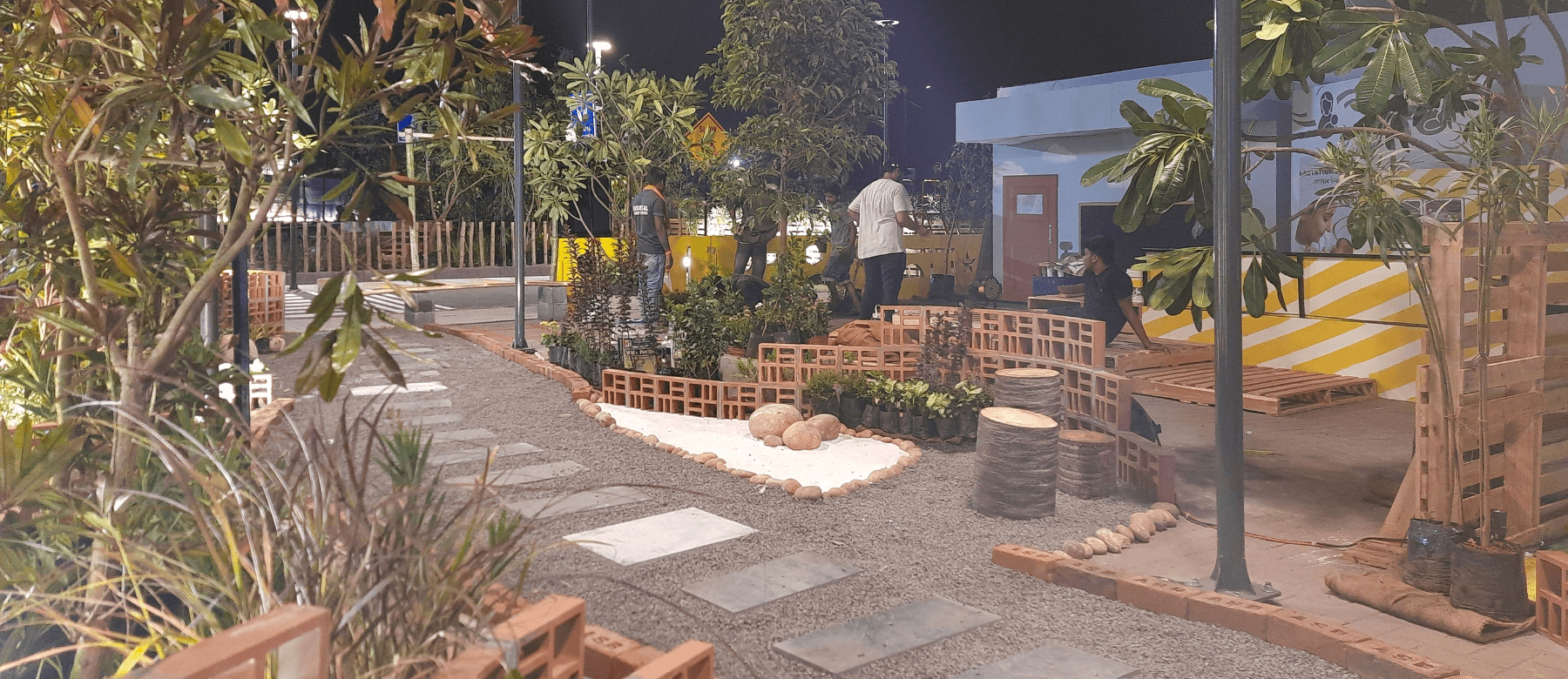

Figure 2: A model street created at the Smart Cities Smart Urbanization 2022 conference incorporating all safety measures such as signages, streetlights, traffic calming measures such as painted junctions, painted cycle and pedestrian tracks, and plantation buffers at the street edges. Photo by WRI India.

Figure 3: A green street edge segregating the pedestrian and vehicular lanes to ensure pedestrian safety. Photo by WRI India.

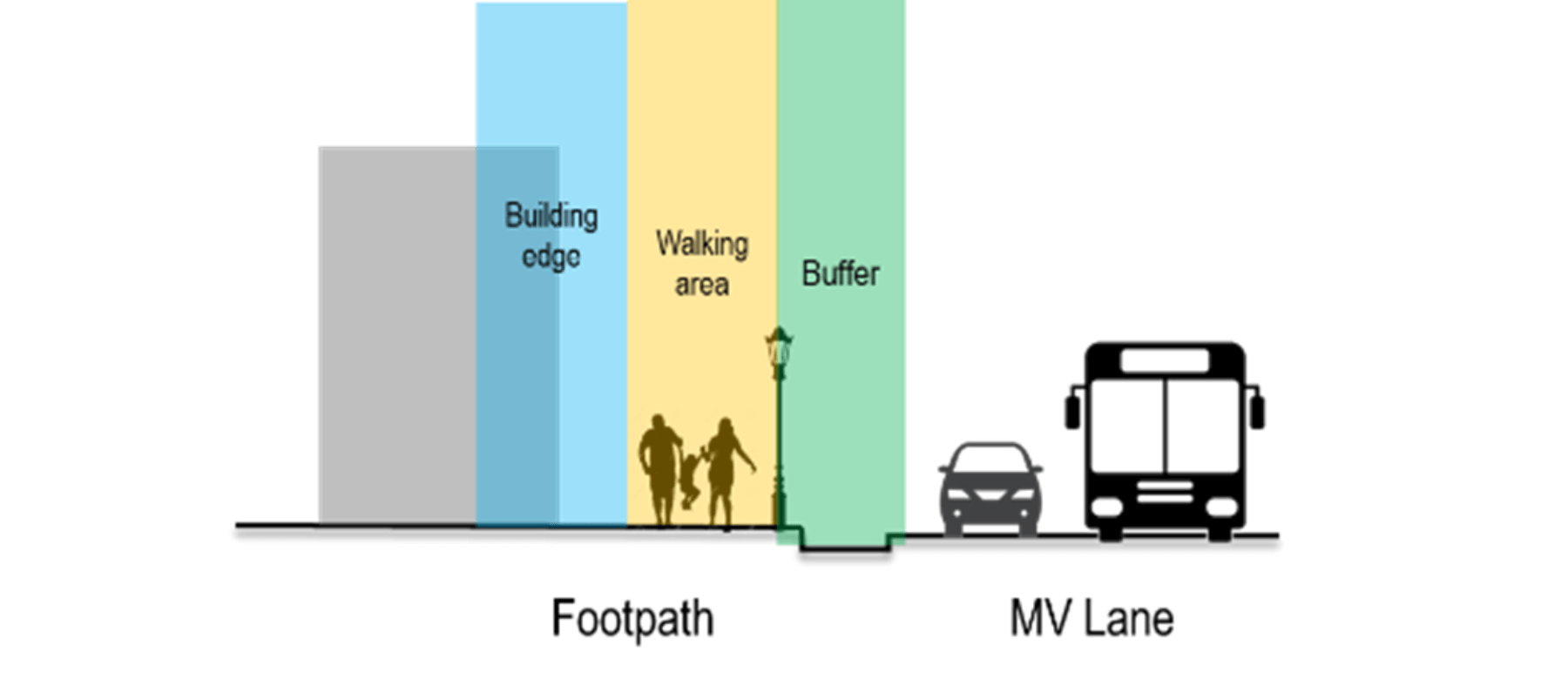

Figure 4: The diagram shows an example of a street section with a dedicated walking track/footpath along a busy road. Visualization by WRI India. - Walking environment: The walking environment is determined by a continuous footpath and adequate buffer between the street and the footpath for safety. These spaces should also have seating for young children, caregivers and the elderly. Neighborhood bus stops, entry to parks and gardens, and pick-up/drop-off points to schools can also serve as pause points along the street.

Figure 5: Alternate pedestrian pathway offers pause points along the way, designed to offer a sensory experience and aid in rainwater percolation. Photo by WRI India.

Figure 6: Prominent zebra crossings near early childhood facilities, parks and gardens are critical to ensure road safety. Photo by WRI India. - Clubbing neighborhood services: Ancillary facilities such as Anganwadis, public health centers, municipal schools and parks can be clustered together to improve access. Furthermore, the streets connecting them should also be developed as slow streets. Bus stops can be made safer and inclusive by adding lactation cubicles, toilets and diaper changing stations.

Figure 7: Anganwadi and primary school play spaces segregated as per age specific needs for play. Photo by Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs. - Access to nature and sensory play: Sensory elements nurture and positively affect the physical as well as mental health of children and adults alike. Streets, neighborhood parks and community vegetable gardens all offer opportunities to connect to nature through elements such as sand, flowering plants, repurposed wooden logs, etc. From sensory play in anganwadi to boost the brain development of young children to active play for older children, neighborhood areas should cater to different kinds of play.

Figure 8: A child plays with a play installation at the exhibition. Photo by WRI India.

Figure 9: A nature-based sensory play space created at the exhibition. Photo by WRI India.

Figure 10: An aerial view of the pavilion. Photo by Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs.

How to curate an immersive learning experience for capacity building?

This experiential learning module, piloted at the Surat Smart Cities Smart Urbanization conference, can easily be replicated across cities by using materials procured by urban local bodies or utilizing low-cost recycled materials. For the learning module to be successful, the following must also be considered:

- Interactive guided tours: Guided tours can be conducted to take the officials through different design components and discuss salient features, followed by Q&A sessions to make the tours interactive.

- Information standees: These can provide more information related to various design considerations that center pedestrians, cyclists, caregivers with young children, women, persons with disabilities and the elderly.

- Resource directory: Standees and information boards can integrate QR codes that direct people to webpages hosting relevant resource material.

- Callouts: Call out boards can be installed at key elements to highlight their advantage. For example: call out boards can be used to classify elements such as the see-through compound wall for gardens, sensory play elements in Anganwadis, pause points with seating, etc.

Such an experiential model has several advantages. It helps demonstrate how quick and simple placemaking exercises can transform the public realm. It does not pose a burden on the exchequer as it uses low-cost materials. It allows the testing of the design before execution and is nimble enough to incorporate feedback from all key stakeholders. Lastly, it highlights the importance of bringing together the right set of professionals to co-create the best solution for strengthening the future of inclusive and equitable cities.

Jeenal Sawla is the Principal Advisor, Data Analytics & Management Unit, Smart Cities Mission.

All views expressed by the authors are personal.