Reinventing urban waterfronts in Indian cities: Five ideas to step-up the way forward

Water is an important defining element of settlements across the world and can be traced back through a city’s historical structure and morphology. The relationship between a city and its waterfront is unique and always changing, depending on the functions carried out on adjoining land.i

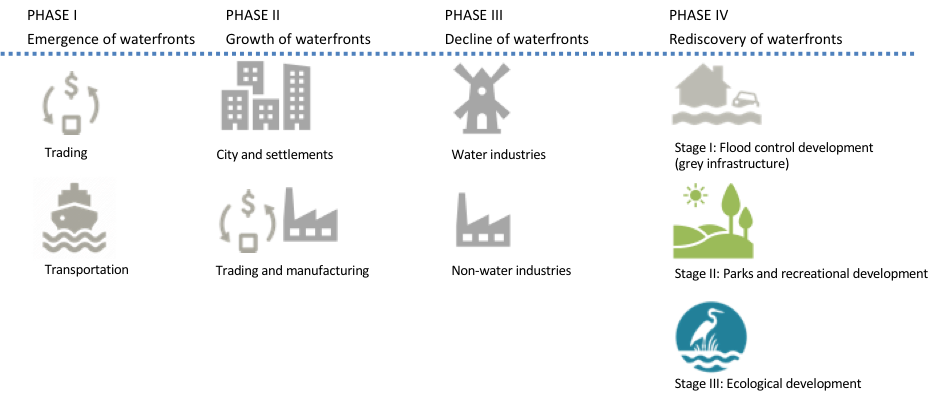

Oxford dictionary gives the meaning of urban waterfront as ‘the part of a town or city adjoining a water body such as a river, lake, harbour, sea etc’. As a phenomenon, urban waterfronts are quite diverse in the Indian contextiii. While, Indian cities saw similar changes on its urban waterfront development (see Figure 1-Phase I and II), sociocultural and religious elements have also always been inextricably woven into this urban edge. In the last few decades, Indian cities have undergone rapid transformation due to globalization and urbanization, leading to the deterioration of their natural water features (see Figure 1-Phase III). Most cities have their back to the urban waterfronts, severing the connection between its people and water.

Since the last decade, there has been a wave of urban waterfront development (UWD) projects being undertaken in India. But every UWD project so far is focused primarily on the built environment (construction, landscaping and beautification) along the water and the potential economic benefits to be derived from them. There is limited consideration of the social, hydrological, environmental and ecological concerns of these projects. Ignoring these aspects of urban waterfront developments can prove detrimental in paving way for a more water-inclusive development.

Each urban waterfront has its own environmental, political, climatic and sociocultural context—there is no one solution for its development in all these spheres. Yet solutions should aim to be environmentally sensitive, socially inclusive and climate adaptive (see Figure 1-Phase IV). Learnings from some global UWD projects could be a useful guiding tool to figure out step-up ideas for future Indian UWD projects. Following are 5 key step-up ideas for unlocking sustainable developmental dividend potential of India’s urban waterfronts:

1. ‘Place’ making = Urban blue green space + people

An urban waterfront has a special place in the modern resident’s heart because it connects them with nature. Wild Mile Chicago, a rewilding project by the local government illustrates how an urban water edge can enhance the association of its city with water (see Figure-2). Fostering people’s interaction with the water-land interface, also seen in the case of restoration of Seoul’s Cheonggyecheon riverfront, lends it a distinct character. Hence, equitable access to urban waterfront if ensured at all times, proves fruitful.

In doing so, preserving the heritage and historic fabric of the city’s urban waterfront and its past connection with water should also be considered. A mixed-use development plan, celebrating the rich history, along the urban waterfront can make the place vibrant. Singapore’s Marina Bay project (see Figure-4) added cultural elements like museums, theatres, convention halls, hotels, commercial establishments, etc. along the urban waterfront. This diversifies usage of the space and livens it up.

An understanding of the broader context of how the society is involved in and around the urban waterfront area helps create inclusive spaces. This in turn fosters an area that is conducive of a plethora of socioeconomic activities. In order to develop and maintain this dynamic nature, these cities designed optimum and equitable public access. This meant that a continuum of pedestrian walkways (see Figure-4) and non-motorized transport to link people to these spaces was ensured.

2. Collaborative Governance

Developing an urban waterfront sees diverse sets of actors and organizations (Government, Private, Public, Services) come together. They are directly or indirectly dependent on this space and identifying their roles and interests at the inception of a project can be useful. Involving them through innovative and interactive governance mechanisms, like the multi-stakeholder engagement as illustrated in Seoul’s Cheonggyecheon riverfront, is valuable for holistic and inclusive transformation of any urban blue-green space.

A top-down or closed-door decision making which is seen in the case of dockland regeneration of Albert Docks, Liverpool can be problematic. Such sites can easily become centers that attract the private sector and their vested interests, and therefore, lead to conflicts which might slow down the development process. A more bottom-up and participatory approach, as observed in the case of Amsterdam, with city leadership buy-in, might help in removing such road blocks, speed up approval process, and create mutual benefits for all stakeholders.

Collaboration between local government, planning and development authorities, and residents can help pave the way towards an inclusive and active urban waterfront management. Setting up of interdepartmental bodies, like the special purpose vehicle or waterbody improvement trust/group, can also facilitate smooth collaboration between stakeholders.

3. Environment always at the heart

Ideally, urban waterfronts should be developed keeping nature and ecology at their heart. In the cases when they are not, it can prove to be detrimental to the surrounding environment like in the case of Ahmedabad’s Sabarmati riverfront. It is important to remember that the development of public spaces should happen in close association with environmental restoration, like in the case of the Cheonggyecheon riverfront (see Figure-5). The proposal of any such regeneration project should take environmental and climate change impacts into consideration at the ideation stage itself, as it can influence the project cost estimation. As observed in Wild Mile Chicago, projects should aim for low impact and resilient design which will most importantly improve the quality of water and help adapt to any future climate vulnerabilities.

4. Financial viability and sustainability

Financing is one of the major challenges that urban waterfront projects face. Since the nature of most such projects is ambitious, and local governments lack the required funding, in many cases secondary sources are sought. The operations and maintenance cost of the project also play a key role in deciding the financial viability of such large-scale urban developments. Innovative funding options and partnerships involving the private sector have been tried by Singapore, Seoul, London, New York, etc. They feature a combination of phased land sale and value capture, TDR and zoning incentives that helped the local government generate revenue through the private sector.

The financial success of urban waterfront projects lies in identifying multiple avenues for revenue generation. Combinations of direct (incremental revenue generation) and indirect (environmental and social) benefits should be considered together as return on investment.

In London, POP’s (privately operated Public Spaces) are urban commons which are maintained and operated by private actors with local community consultation and under city government regulations. While such management models might be financially beneficial, they should be handled with caution as they can lead to unwanted privatization of urban commons.

5. Organic Transformation

Any regeneration project is time intensive so aiming for short-term benefits might not be sustainable. The development should seize the benefits of as many low-hanging fruits, but long-term vision is indispensable. Instead of a masterplan approach, a strategic vision which frames the shared community interests for the place are more holistic. Although a masterplan (a statutory document) for development helps by safeguarding it from political cycles, but its rigid nature hinders organic transformation that is incremental and flexible to the changing needs of the city and its people. A shared vision is adaptable and can be implemented gradually, starting with small changes, guiding developments as the transformation of the urban waterfront gains credibility.

Sustainable development of urban waterfront involves a number of physical and social considerations. With this intention, National Mission for Clean Ganga (NMCG) has developed a high-level guidance framework integrating water, ecology, environment and climate resilience related considerations within the existing framework of urban riverfront planning and development. Patna riverfront is one of the first riverfront development project under NMCG, which successfully addresses urban waterfront development as a collaborative and multi-layered enterprise (see Figure-6). A balanced approach to urban waterfront development, where ecological, environmental and water concerns are addressed harmoniously along with development can accrue multiple benefits to people and ecosystems while generating economic dividend for Indian cities. With these 5 step-up ideas, the upcoming urban waterfront projects in India can leverage the value of the treasured urban blue-green asset for the city and its people.

i Bhavna V., Waterfront and Its Relationship to the City Structure, 2016

ii Redzuan, N., & Latip, N. S. (2016, July). Principles of Ecological Riverfront Design Redefined. Creative Space, 4(1), 29-48

iii Joshi, D., Fawcett, B. Water, Hindu Mythology and an Unequal Social Order in India.1990.