Public-Private Partnerships (PPP) in City Bus Services in India: NCC and GCC

This is first in a series of blogs on Public Private Partnerships in city bus services in India.

Public Private Partnerships (PPP) in city bus services in India have been prevalent for many years now, but they have gained momentum in the last two decades. The renewed adoption of PPPs started when several small and medium sized cities, that lacked technical and financial resources, initiated bus services for the first time. PPPs emerged as a way for these cities to combine public sector’s expertise in planning and managing a bus service with private sector’s capabilities to access finance and introduce cost effectiveness in bus operations and maintenance (O&M).

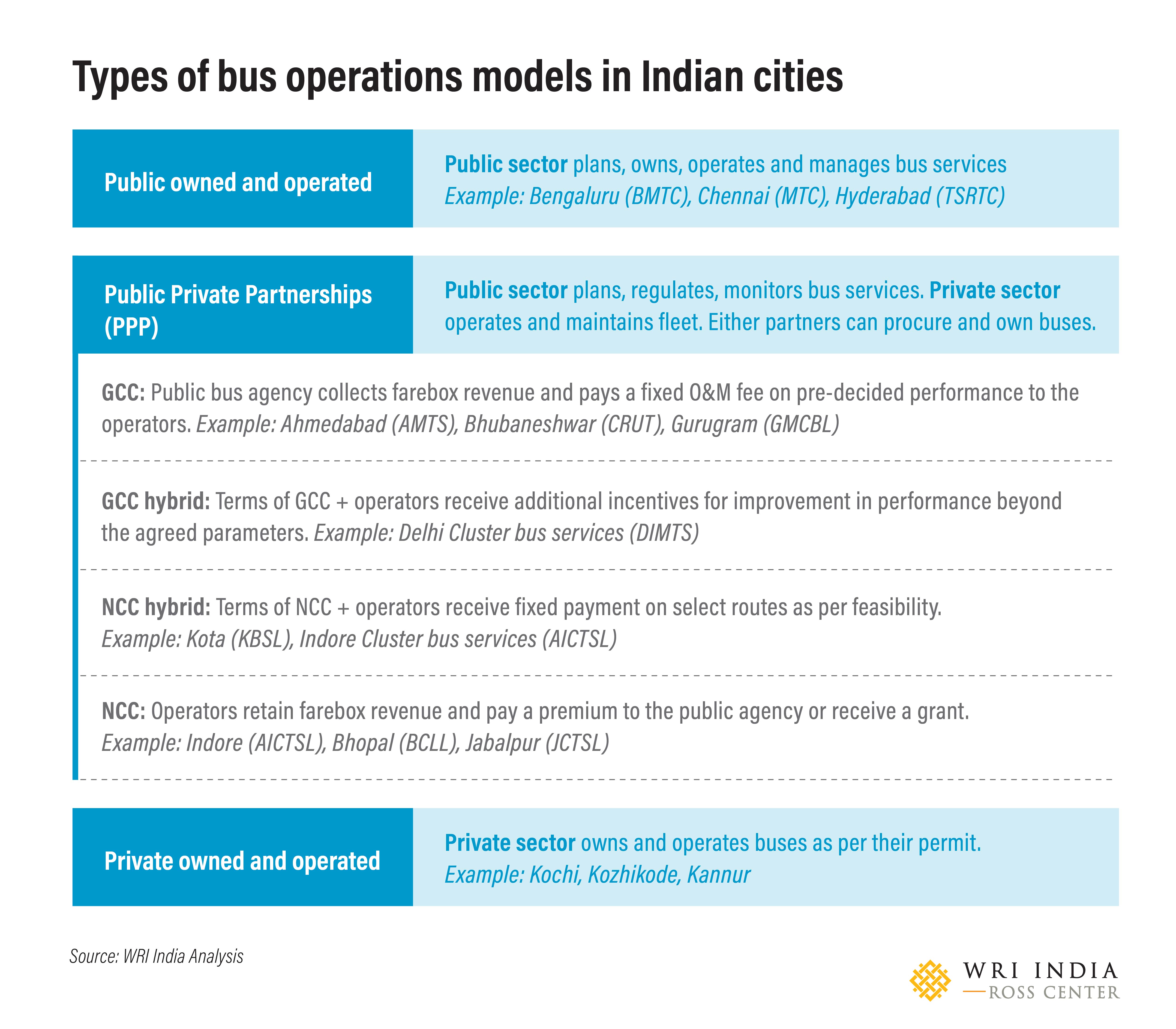

PPPs follow either a Net Cost Contract (NCC) or a Gross Cost Contract (GCC) or their hybrids (figure 1). In all, public sector is tasked with bus planning and management and private sector is responsible for bus O&M. The difference lies in distribution of risk among the two stakeholders. Risk is introduced by the allocation of responsibility of passenger fare collection as the main source of income. This blog examines the two types of PPP contracts, their use to implement city bus services over the last two decades, their success and the potential challenges of each.

NCC: Balancing Profits and Service Quality

In NCC, private operators are responsible for collecting passenger fare, which is their income for bus O&M. As per route profitability, private operators either pay a premium to authority or collect a fee from them.

In 2006, Indore started its city bus service using NCC. Within a year, it upgraded its skeletal services to a fleet of 110 buses. Indore’s rapid bus deployment and established assurance of receiving a fixed premium from operators prompted other similar-sized cities such as Amritsar, Jodhpur, to adopt the Indore Model — a reference to the NCC variant — to structure their own service models. These were also the cities that received funds from Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission to operationalize buses.

However, after initial success, services in most of these cities either plateaued or were terminated. The cities failed to contextualize the model to their local conditions, lacked technical capacity and depot spaces and adopted poor planning. This led to inadequate services that had lower ridership, diminishing operational viability for the private operators. For example, in 2010, operators in Aurangabad terminated services to avoid losses from low ridership which in turn was from poor route planning and lack of depots.

To meet their costs or to generate profits, operators in these cities, including Indore, modified routes, overloaded buses and skipped bus maintenance. The resulting services were unreliable and unsafe with few takers leading to cyclic reduction in ridership and revenue. This is a typical eventuality for NCC model as revenue from passenger fares, which is kept affordable, does not always cover the mounting costs of operating buses.

GCC: Ensuring service quality

With the realisation of limitations of NCC in ensuring service quality, cities started to opt for GCC. Under GCC, the public agency retains the responsibility of fare collection, in addition to service planning and management. Private partners receive an assured and mutually agreed fixed payment for bus O&M. GCC allows public agencies to have greater control over service quality, as payments to operators are linked to service performance.

Cities, however, face technical challenges in measuring performance and enforcing related penalties and incentives. Public agencies also depend majorly on passenger fare revenue to pay operators. If collected revenue is insufficient, payments to operators are often delayed, who in turn, suspend services.

Bhubaneshwar, which started bus services in 2018 on a GCC model, has overcome this challenge by securing annual financial support from the State Government. The city SPV, Capital Region Urban Transport, has also outsourced major functions such as ticketing, revenue assurance and quality assurance, to reduce expenses.

Aurangabad restarted its bus service on GCC in 2019 by contracting operations to another public sector undertaking — Maharashtra State Road Transport Corporation (MSRTC). In doing so, the city avoids higher operational costs due to inbuilt profit margins of private operators. It also eliminated the need to invest in depots by leasing existing MSRTC depots. MSRTC receives payments on actual expenses incurred by them for bus O&M.

Making PPPs Work

PPPs have emerged as a way for cities that lack financial resources to introduce or scale bus services. With a burgeoning demand for mobility, PPPs hold the potential to serve as a solution to cover the investment needs of the bus sector and ramp up bus services.

However, irrespective of the adopted model, almost all cities have faced challenges with PPP in achieving desired service quality levels to make it ubiquitous. The full potential of PPPs in bus operations can be realized by ensuring alternate revenue generation sources, adopting data based planning practices, improving monitoring mechanisms, strengthening tendering and contracting and building technical capacity. These interventions will be discussed in detail in the next blog.

Read the second blog in this series here.

Udit Khandelwal is an EPP consultant with the Sustainable Cities and Transport program at WRI India.

Views expressed are the authors’ own.